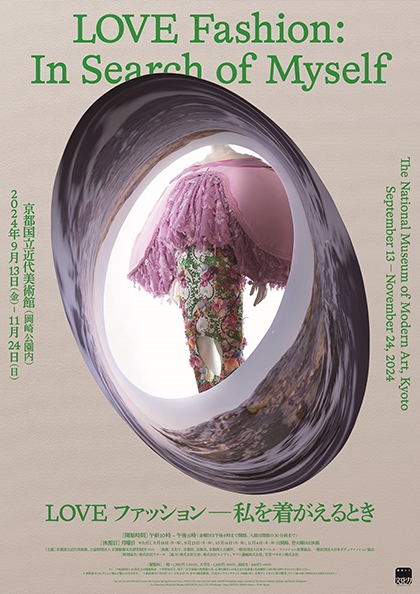

Dressing is a universal human activity. The clothes that we wear embody or conceal our internal desires, and they can reveal those desires along with our longings, our passions, and the conflicts and contradictions that we face. Fashion has a role as a receptacle for ‘Love’: the passions and aspirations of the wearer. Driven by those emotions, we may be motivated to wear something that we like, be inspired by someone’s look, want to be ourselves, or just want to lose ourselves.

This exhibition is based on clothes and other fashion items from the KCI’s collection of costume from the eighteenth century to the present day. In conjunction with art and literary works that throw light on fundamental human drives and instincts, the exhibits encourage us to ponder the various forms of ‘Love’ that can be seen in relation to fashion. Through this exhibition, we gain an opportunity to think about and reevaluate what it means for humans to wear clothes.

Exhibits and Sections

This exhibition consists of approximately 100 clothing, 20 accessories, and 40 artworks in five sections. The exhibits encourage us to ponder the various forms of ‘Love’ that can be seen in relation to fashion.*Certain objects are displayed for a limited venue and period only.

*Unless otherwise described, exhibits are selected from collection of the KCI.

1.Born to Be Nature

I want to spend my life surrounded by flowers. I want to feel the warmth of living creatures. A sense of longing or a loving respect for nature, and the desire for nature to keep nature close at hand, are feelings that people have always had, whenever or wherever they lived.

People in ancient Greece and Rome adorned themselves with garlands or headpieces made from fresh flowers, while during the same period, people in China depicted flowers which would remain fresh forever by embroidering onto fabric. Eighteenth century European nobility—regardless of gender—vied to be the most brilliant in court by dressing themselves in garments that featured embroidered or woven floral patterns. And in the present day, we are not only drawn to flowers for their beautiful colors and shapes, but we also project, onto flowers, attributes such as as love, blessings, hope and peace, incorporating such sophistication into our clothing.

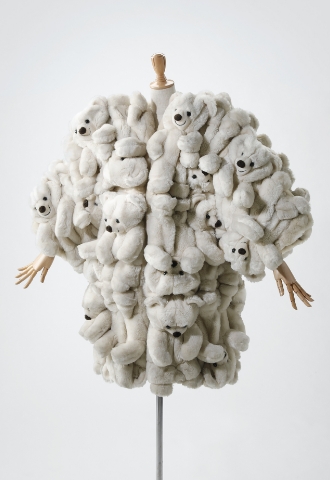

Fur was one of the first materials used in clothing that nature bestowed on humankind. Our ancestors had to protect themselves with the skin and fur of animals to compensate for the elimination of body hair, the purpose of which was to protect our evolving cerebrum from heat. Perhaps due to an envy of, or obsession with what has been lost since ancient times, we have been infatuated with the touch and warmth of fur, while we have adorned our clothing with bird feathers and gathered beautiful and rare materials from around the world, which in turn has triggered the extinction of countless species and the destruction of ecosystems.

Nature now needs to be protected. As a result, our affection and love for nature is even deeper. Jean-Charles de Castelbajac and Stella McCartney’s ”fur-free fur” coats convey our deep affection for fur, which could almost be described as perverse. The emotions that we seem to retain with respect to our remaining body hair are evident in the works of Motohiko Odani, who uses human hair as his material. When exactly will we be able to return to nature?

Le Monnier (Jeanne Le Monnier), Beret with staffed bird, c. 1946. © The Kyoto Costume Institute, photo by Masayuki Hayashi.

J. C. de Castelbajac (Jean-Charles de Castelbajac), Coat, Autumn/Winter 1988. © The Kyoto Costume Institute, photo by Takeru Koroda.

2.Dress Me Up

We find ourselves tossed to and fro every day between an admiration of beauty and a feeling of failure in being able to see beauty. The shape of clothing through the ages reveals the imaginative depiction of diverse forms of beauty which were pursued during different periods in history. These include gigot or leg-of-mutton sleeves which were so exaggerated that they were larger than the wearer’s face, the S-bend waist created with a tight-laced corset, and the skirt that spread out so widely by wearing a crinoline underneath, that the wearer could barely walk. Christian Dior and Cristóbal Balenciaga went on to reference these looks which appeared during the nineteenth century. The outstanding beauty of form of their designs took the the world by storm, while Commes des Garçons presented a form of beauty that was completely different from the symmetrical balance of the Western image of the body. The history of modern fashion is arguably a chronicle of responses to beauty as imagined by the individual and the resulting embodiment of a process of transition and repetition.

The contradiction of humans who crave, and yet at times resist, beauty. Living in today’s modern age, the excessive attachment towards form and the physical body evident in fashion of the past appears bizarre and incomprehensible. However, what about the all too familiar diets, the retouched photos, and cosmetic surgery today? The hesitancy and self-consciousness as we get on the scales, the joy and the sense of unease when we get likes for our selfies, and the fear and elation we feel as we lie on the operating table. Tomoko Sawada’s ID400 homes in on the discrepancy between external appearance and what lies within. It is arguably a work that captures this all too common perversion by tracing our desire for and aspiration towards beauty.

Throughout history, we have diligently tried to be beautiful. These efforts have sometimes been attempting to inspire, sometimes competing with others, and sometimes blacking oneself out. Today too, there is a part of us that is screaming out the words “I want to be beautiful.”

Christian Dior (Christian Dior), Evening dress, Spring/Summer 1951. © The Kyoto Costume Institute, photo by Takeru Koroda.

Balenciaga (Cristóbal Balenciaga), Evening dress, Winter 1951. ©The Kyoto Costume Institute, photo by Takashi Hatakeyama.

3.Just the Way We Are

We also feel the desire to just be ourselves as we play various roles in society. Will we ever be able to realize the dream of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who, back in the eighteenth century, advocated naturalism and pursued the ideal of depicting the natural self.

The 1990s was a time when the photographs of Wolfgang Tillmans who captured the everyday lives of his friends resonated with many, while the designs of the garments shown by emerging brands of the time such as Prada and Helmut Lang were based on our actual physical shape, rather than the idealized physical forms which were an extension of traditional Western aesthetics. These designers’ garments represented the human form, brazenly revealing glimpses of dowdy underwear, and represented a positive acceptance of the ordinary.

The questioning of accepted values and the aim towards a coexistence of diverse values are not unrelated to the “body positive” movement that began to intensify from the early 2010s and the “body neutral” concept which followed. While the keyword “diversity” was tied to these two trends and had a massive social influence, it also conveyed the challenge and difficulty of accepting one’s body “as is” and raised the question of what exactly the natural self represents. In Tomona Matsukawa’s paintings which depict the reality of women living in these times, we have a glimpse into the reality of the complex society in which we find ourselves.

Nensi Dojaka (Nensi Dojaka), Dress, Autumn/Winter 2021. ©The Kyoto Costume Institute, photo by Takeru Koroda.

Tomona Matsukawa, Nevertheless, I am a mother, 2018, Private collection. © Tomona Matsukawa, courtesy of Yuka Tsuruno Art Office, photo by Ken Kato.

4.Break Free

Language, nationality, ethnicity, religion, culture, class, occupation, age, gender differences….as a part of this predetermined narrative, we often use clothing to project an identity to define a self that is in fact non-existent. It is arguably because we can talk about ourselves through clothing as language (= metaphor) that we can position ourselves within society or share how we feel with others.

Clothing can be eloquent, but at times it becomes associated with “me” and binds us to that narrative. We share a desire to escape from such a “me” narrative. Virginia Wolf, in her novel Orlando (1928), was a pioneer in her attempt to depict the release from our inherent identity and to have choices through a story of the transformation of the subject, much of which was associated with her change of clothes. Rei Kawakubo has always presented alternative designs that go against uncomfortable restrictions and are based on her intuitive insights into the period, and she has always left it to the wearer to determine the experience of wearing the clothes. The trilogy of Kawakubo’s Orlando designs—her women’s collection, men’s collection and costumes for opera—represents her reconstruction of Orlando through her unique interpretation of that work. Arguably, they indicate the extent to which Wolf, who struggled as she lived in an oppressive society, resonated with a designer who remains the flag bearer of innovation and liberation. These “women” transcend time and resonate with each other in celebration of the story of Orlando who struggled with her transformation some 400 years ago and who shook off the idea of dressing up as “me.” Freedom is not so much a desire for an imaginary utopia, but a statement—that it is, in fact, our very own life as “ourself” that undergoes change on a daily basis.

5.Take Me Higher

I am me. But I am dreaming of myself as someone that is somehow different from the way I am now. Humans have had a desire to transform themselves into another creature that is not human, as seen in the clothing of designers such as House of Worth and Alexander McQueen. Or experiencing the pleasure of being our other self in a new virtual reality through games or on social media, in which we have separated from our bodies and attributes, as in the designs of Balenciaga or Threeasfour. And, as the result of clothes which are not clothes, such as the designs by Tomo Koizumi featuring frills or Viktor & Rolf featuring ribbons, which have risen above the type of clothes that we wear in our everyday lives, we can experience the excitement of imagining how we would feel if we were to wear a certain garment, or to experience the feeling of being someone different from oneself when we put on a garment, or the ecstasy of encountering a self that is more like oneself. Clothes have the power to cast a spell on each and every one of us.

It is difficult for people to stop feeling this way, having these sensations. Even the garment that you yearned for, the garment that you thought was perfect for yourself, will suddenly seem jaded, after which you go on to seek another new garment. It is as if you have been taken over by something that is not yourself, and something that is not you has taken control of you. Like Hans Christian Andersen’s Red Shoes or like a Loewe garment in which the body has been taken over by lips.

Perhaps we are projecting our interminable human desire onto the hermit crabs that change their “dwelling,” like the crabs that appear in AKI INOMATA ’s Why Not Hand Over a ‘Shelter’ to Hermit Crabs? The spell of clothes and our never-ending desire. When the “I” that had been forgotten returns after being released from the spell cast by clothing, perhaps we come under the spell of a new kind of magic. Or perhaps magic is the hell that is never-ending human desire.

Loewe (Jonathan Anderson), Dress, Autumn/Winter 2022. ©The Kyoto Costume Institute, photo by Takeru Koroda.

Balenciaga (Demna Gvasalia), Armor and Shoes, Fall 2021

Look 50, Afterworld: The Age of Tomorrow, Balenciaga Fall 21 collection, Courtesy of Balenciaga